Keeper (2025) by Osgood Perkins is a hypnotic, dread-soaked cabin-in-the-woods riff that turns relationship intimacy into a trap, anchored by Tatiana Maslany’s gripping lead performance.

Copyright NEON

Familiar setting, fresh ideas

Osgood Perkins’ latest effort begins like a classic variation on the “cabin-in-the-woods” motif: Liz (Tatiana Maslany) heads out with her boyfriend Malcolm (Rossif Sutherland) to a remote cabin somewhere deep in the forest to celebrate their anniversary. The weekend is meant to be romantic, but from the very start it’s clear something is off. Perkins doesn’t turn this premise into an action-driven horror scenario; instead, he focuses above all on the setting: artful dissolves, striking motifs, and visual flourishes dominate the screen. The forest surrounding the cabin is both backdrop and performer. It feels as if it’s constantly peering into the house from the outside—threatening, violating the characters’ privacy. The cabin itself is a highlight, too: its triangular architecture (which Perkins presumably cribbed from his own film Gretel & Hansel (2020)) and its imposing wooden walls become an eerie, claustrophobic labyrinth—one that soon seems to offer Liz no way out…

As in The Blackcoat’s Daughter (2015) or I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House (2016), Perkins once again commits fully to a female perspective; Maslany thus slips seamlessly into his “female horror canon,” a through-line running across his filmography. Keeper works—like so many Perkins films—again as a dark fairy tale in which evil functions as metaphor. In its forest- and gender-paranoia, the film recalls Alex Garland’s Men (2022), but also Colin Minihan’s relationship thriller What Keeps You Alive (2018): love as a trap, intimacy as a laboratory for power.

Disgusting Maleness?

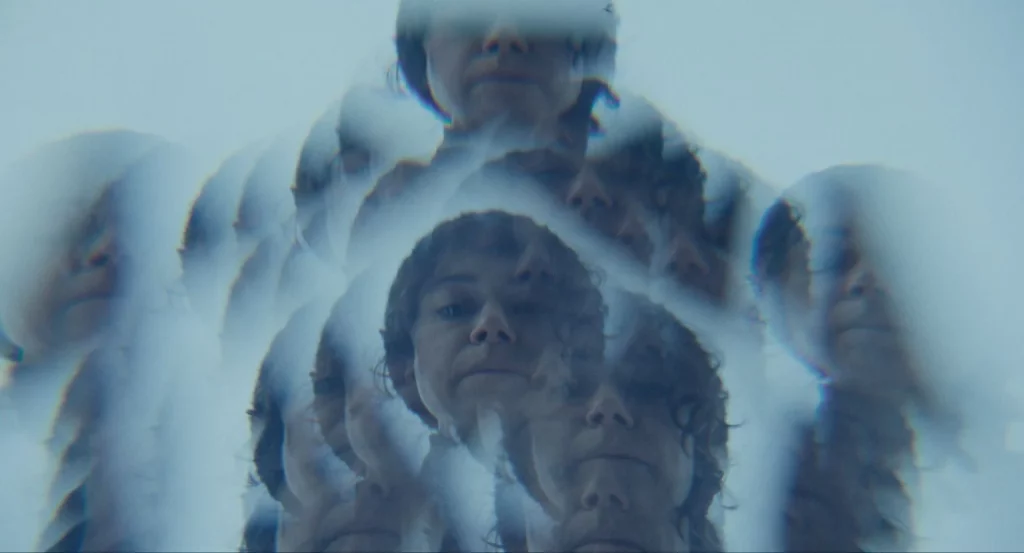

Perkins himself rather unironically names the film’s core as a look at “disgusting maleness”—a study of how ugly masculinity can become when it turns to preserving its privileges. That’s true—but only half the story. Because Keeper doesn’t just tell a disturbing fairy tale as a commentary on toxic masculinity, one that only really hits full speed at the end; above all, it’s a worthwhile stylistic exercise in experimental horror. Perkins’ spare but effective direction, which at times recalls the enigmatic style of David Lynch, is complemented brilliantly by cinematographer Jeremy Cox, who delivers some impressive images here. He strings unsettling scenes together and, precisely through long dissolves and layered planes of imagery, creates an elusive, almost poetic mood. Perkins and Cox are also masters of negative space; they exploit it to the fullest in order to generate maximum unease.

Still, anyone unwilling to settle into Perkins’ rhythm may grow restless in the first half: Keeper bets radically on atmosphere, on omission, on the quiet tipping of normality. (Some reviews criticized the film for stretching its idea too long.) And yet the patience pays off, because in the end Perkins unleashes a finale that genuinely rearranges familiar cabin horror. Not as meta as Cabin in the Woods (2012), but just as determined to deliver something idiosyncratically new. A strangely beautiful, highly original film: a dark fairy tale that unfolds quietly, piece by piece—only to eventually explode.